What does it take for new inland ports to succeed? This white paper aims to answer this question, based on the use of case studies and underlying freight trends. We offer, in closing, a ten-point checklist of key success factors in the planning and preparation for new inland ports.

Inland ports – multimodal facilities paired with distribution centers located far from the sea – have sprung up around the United States, particularly over the past decade. Recent growth is tied to extension of the international transport efficiencies generated by containerized cargo shipments to landlocked points, and reflects, most simply, the vast size of the landlocked American interior; two-thirds of our 50 largest cities are located away from the sea. These inland ports are at varying stages of development. Some have evolved into extensive logistics hubs that combine warehousing (often with a foreign-trade zone (FTZ) designation) and distribution with rail intermodal, truck, barge, and in some cases, air freight operations. Inland ports and logistics hubs generate local economic benefits, in the form of jobs, spending and taxes, as well as distribution efficiencies for shippers and consumers.

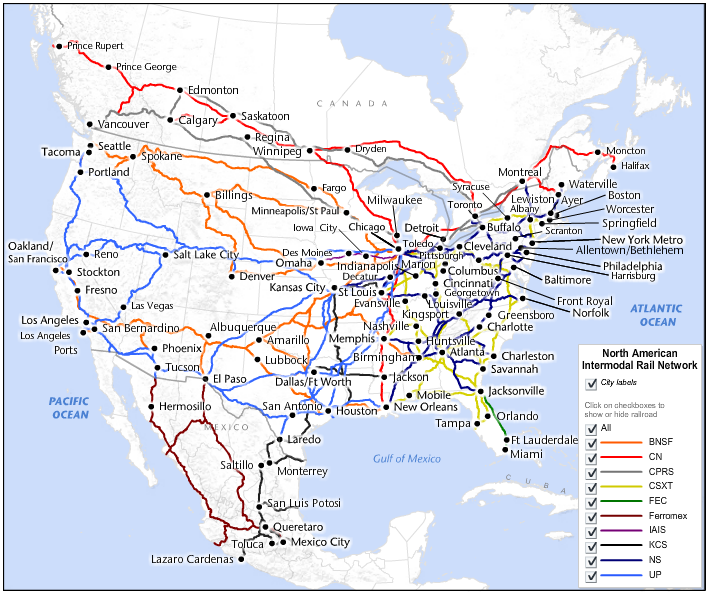

Intermodal hubbing across the US and Canada

Several types of inland ports have been developed, each with a dominant purpose or transport mode. Some of the earliest examples sprang from the need for local communities to re-purpose Air Force bases slated for closure by the US Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) commission during a series of recommendations in the 1989-1995 timeframe. These tended to be air freight oriented and included locations near San Antonio, Columbus and Kansas City. Unrelated to the BRAC, but also air-oriented, the Alliance Airport opened on Dec. 14, 1989 as the cornerstone of what would become the mega logistics cluster at Alliance TX (profiled in more detail later).

A second type were developed as an extension of marine terminals, with the main intent being to ‘bring the port to the customer’ to better compete for hinterland traffic, while also alleviating congestion and enhancing capacity at ports where expansion can be difficult due to costs, environmental issues, and lack of available land. One of the early examples is the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) at Front Royal, Virginia, established by the Virginia Port Authority (VPA) in 1989 on formerly rural farm land. The VIP is located on 161 acres, adjacent to a Norfolk Southern main line, and is accessible via interstates 66 and 81, some 220 miles from the Port of Virginia’s coastal facilities. Although the relatively short rail length of haul was unusual at the time the port was established, close collaboration between the VPA, the State of Virginia and Norfolk Southern drove the development forward.

The third type of inland port is dominantly rail-oriented, typically further from a seaport, and can evolve into an extended ‘logistics cluster’ or ‘freight village’ with dozens of facilities. An early example is Kansas City’s SmartPort, planned in the late 1990s (profiled in more detail later). A more recent example is the Joliet Intermodal Terminal, the Union Pacific’s $370 million terminal opened in 2010, developed in conjunction with CenterPoint Intermodal Center-Joliet.

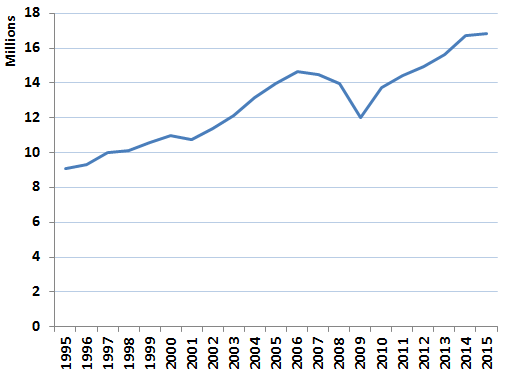

Growth of intermodal rail

Rail intermodal traffic has grown sharply in the US and Canada, from humble beginnings in the 1950s as “piggyback” truck trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) shipments. TOFC slowly expanded, but real growth accelerated when double-stacking of containers was introduced in the early 1980s, driving favorable economics and increasing security. Today, there are approximately 190 intermodal ramps in the US and Canada (Figure 1), with the four major U.S. Class I railroads each serving several dozen locations. Many are at inland points.

Figure 1. North American intermodal rail terminals

Source: Intermodal Association of North America (IANA), 2016.

The volume of US and Canadian rail intermodal shipments continues to rise. A compound annual growth rate of 3.1% was registered from 1995 to 2015 (Figure 2). This rate of growth considerably exceeds the expansion of the US population (1.1% annually) over this time frame. The downturn in volume that occurred during the 2007-2009 recession reversed from 2010 onward and a new record was set in 2015.

Figure 2. Growth in US and Canadian intermodal rail shipments

Source: American Association of Railroads (AAR), Railroad Ten-Year Trends, and Weekly Railroad Traffic

What makes for successful inland ports?

Successful Inland intermodal facilities are typically located near major population centers (such as Atlanta), or at crossroads of multiple rail carriers (such as Kansas City or Memphis), with the largest and most active locations having both these attributes (Chicago, Dallas). These locations are convenient to interstate highways for trucking access, and often located well outside the city center to benefit from reasonably-priced land (e.g., Joliet, outside Chicago; Alliance, outside Fort Worth).

The space required for an intermodal ramp varies from as little as 40 acres (e.g., Kansas City Southern’s terminal in Jackson MS is 47 acres; the initial footprint for the Greer SC inland port was 37.5 acres) to close to 800 acres for each of the Joliet, IL (about 40 miles southwest of Chicago) intermodal ramps: BNSF’s Logistics Park Chicago, opened in 2002, and UP’s Joliet Intermodal Terminal, opened in 2010.

Logistics activities such as warehousing, transloading, cross-docking, light assembly and packaging are also typically conducted near intermodal ramps; together these transform the area into a true logistics hub. Continuing with the Joliet example, the CenterPoint Intermodal Center is situated on 6,400 acres and boasts dozens of marquee tenants. With the BNSF and UP ramps bookending the development, the overall to intermodal ramp acreage ratio is now about four to one.

E-commerce, with its need for same-day and next-day delivery from local market fulfillment centers, is a further factor stimulating interest in inland ports. Volumes related to these uses can contribute to the economic viability of a new inland port.

Another good example of space requirements is the recently-developed 318-acre Central Florida Intermodal Logistics Center in Winter Haven, FL. Opened in 2014, it has become a focal point for transportation, logistics and distribution in the Orlando-Tampa belt. The planned layout includes an additional 930 acres, so roughly a three-to-one ratio, available for development of up to 7.9 million square feet of warehousing, light industrial and office facilities.

Selected examples of inland ports

The examples below illustrate some of the key attributes for inland port success. These are drawn from large and smaller operations located in various parts of the country.

Greer, South Carolina

The South Carolina Ports Authority’s (SCPA) $50 million Inland Port Greer opened in November 2013. The plan, developed by the SCPA and Norfolk Southern beginning in January 2012, called for an initial capacity of 40,000 containers per year, on a 37.5-acre site, with the opportunity to expand to 100 acres in the future. The five-year goal was to reach 100,000 lifts. The Greer facility, 212 miles inland from the Port of Charleston, sends and receives trains each night to/from Charleston. It has outperformed expectations. In May 2016, the facility handled 8,620 rail moves and is on track to exceed 100,000 lifts in just its third year of operation. What made Greer so successful so quickly?

According to Jim Newsome, the SCPA CEO (in a release dated April 20, 2016), the three critical components for success of an inland port are:

- An existing mainline, intermodal containerized rail service;

- An anchor client providing a significant cargo base at facility start-up; and

- A willing local community of elected officials, business partners and neighbors.

In the case of Greer, the anchor client is the BMW plant, less than five miles from the inland port, accessible via a rail spur. The plant, which opened in 1994 and has expanded several times, now produces more than 400,000 vehicles per year, with 70 percent exported. In 2015, the BMW plant was the state’s top exporter, the largest US automotive exporter, and the largest facility in BMW’s global production network. Imports of auto parts, including engines and transmissions from Germany destined for the plant, make up a considerable portion of the Greer port’s throughput, ensuring sufficient and steady volumes that support regular train service. In fact, auto parts were the No. 1 containerized import via the Port of Charleston in 2015.

In July 2015 SCPA announced that Dollar Tree had selected upstate SC for a $104 million, 1.5 million square foot distribution center, ensuring the continued success of the inland port. And on April 20, 2016 SCPA announced plans to evaluate the viability of a second inland port facility in Dillon, SC.

Kansas City SmartPort

KC SmartPort is one of the most interesting cases of an inland port and logistics hub in the United States. It is a non-profit economic development organization, rather than an anchor tenant or location. It was conceived in a 1998 study, and is dedicated to fostering the growth of business through efficient transportation and by attracting freight-reliant companies, such as manufacturers and distributors.

Kansas City boasts unique transportation attributes: The nation’s largest rail hub, by tonnage; four Class I railroads; four intermodal parks; four major interstate highways; an international airport; and navigable river access. The public-private marketing and development model has succeeded in attracting numerous industries such as e-commerce fulfillment (e.g., Amazon, and in 2015, ReallyGoodStuff.com and Jet.com) and automotive manufacturing (e.g., GM, Ford, Harley-Davidson, Goodyear, Johnson Controls – about 100 companies in all).

KC SmartPort-related facilities cover an area of roughly 4,000 acres, including potential space for future development. Developers are well-known industrial groups such as Rockefeller, NorthPoint, CenterPoint and Trammell Crow. Some sites are rail-served, others are in proximity to the airport; all are well-served by the major interstate highways passing through the area. KC SmartPort has also paid significant attention to congestion and environmental issues. It has directly addressed both greenhouse gas and particulate air emissions concerns. As a result, combined with its commercial and transportation success, Kansas City can be viewed as one model for inland port planning and development.

AllianceTexas

AllianceTexas is an outstanding example of a visionary, master-planned, mixed-use community, developed by Hillwood, a Perot company, situated on the north side of Fort Worth. The scale is massive, comprising a tract of 18,000 acres that balances industrial, commercial and residential uses. By 2014, more than $7.8 billion of private capital and $600 million of public funding had been invested in the site.

At its heart is the Alliance Global Logistics Hub. This includes an all-freight airport (AFW, opened in 1989, thanks to a partnership between the FAA, the City of Fort Worth and Hillwood) that is used for international and domestic cargo as well as serving as a regional sorting hub for FedEx Express. It is home to Foreign Trade Zone 196 and staffed with US Customs and Border Patrol officers on site to clear cargo. There is BNSF intermodal service, to/from the BNSF Alliance intermodal terminal (~600,000 lifts annually, 16 doublestack trains daily; opened in 1994), as well as carload service. Union Pacific also provides carload service via its mainline on the eastern side of Alliance (its nearest intermodal ramps are in the Dallas area). Alliance lies astride the major north-south interstate (I-35W), and has easy access to east-west highways (I-20, I-30).

Today, Alliance provides a base for 290 industrial companies occupying 25 million square feet of space, mainly distribution oriented. Some 44,000 jobs have been created, and in 2014, it registered its $1 billionth tax dollar generated. With its ambitious scope and scale, Alliance has morphed into something beyond an inland port –an example of a highly successful inland freight node and logistics hub.

Success doesn’t always come easy with inland ports

A word of caution is in order: Inland port concepts do not always take off, or not immediately in any case. The numbers have to work for both shippers and the railroad, and complementary infrastructure and services take time to evolve. Shippers will only use the service if transit times, reliability and cost are attractive compared to truck. On the carrier side, railroads require sufficient volume to offset the cost of a facility, personnel and train operations. The level of volume needed to be viable will vary depending on whether the service will be completely new, or leverage other existing flows, and whether the inland facility will be purpose built or already operates to serve other flows.

For example, using round numbers for illustration, a minimum target volume of 100 loaded containers per train (note that some long-haul intermodal trains typically haul almost three times this level) to support a new service would equate to approximately 10,000 lifts per year for service once per week in each direction (100 containers x 2 directions x 50 weeks). A more robust flow to support 5-day-per-week service might be on the order of 50,000 containers per year (100 containers x 2 directions x 5 days x 50 weeks). The break-even point for a given proposed facility or service will of course depend on a variety of additional factors including monetization of societal benefits and incentives, as we discuss later.

The Virginia Inland Port in Front Royal, for example, while established very early on in 1989, didn’t pass the 10,000 container volume threshold until its 5th year of operation, and didn’t pass 20,000 until its 16th year of operation in 2004. Prince George, the first inland intermodal terminal in British Columbia, focusing primarily on forest product exports from nearby mills, has seen volume plateau at around 20,000 units. Both remain optimistic about future growth. Here are two additional examples.

NC State Ports Authority Charlotte Inland Terminal

According to a 2007 press release by the North Carolina State Ports Authority (NCSPA), its Charlotte Intermodal Terminal on Hovis Street was the nation’s first inland port when it opened in January 1984. It offered shippers “one-stop service,” with the NCSPA providing container loading, unloading and storage, and transportation to and from the Port of Wilmington (about 200 miles away) on dedicated, weekly unit trains operated by the NCSPA’s partner, Seaboard Systems Railroad. However, the volume of international trade at that time proved insufficient to sustain the service, and the train service was discontinued.

Since then, the NCSPA has maintained its Charlotte Inland Terminal, but it is a truck-served facility that provides neutral container yard operations. But two recent developments in Charlotte underscore a renewed interest and enthusiasm for inland ports. In March, Norfolk Southern (NS) started the first scheduled service from Charleston (SCPA) to its facility in Charlotte, connecting through Spartanburg. The 200-acre NS facility in Charlotte opened in 2014 as part of the NS Crescent Corridor initiative, thus the Charleston flows are incremental to the existing volume.

Next, on July 19, 2016, the NCSPA and CSX jointly announced the re-launch of direct Wilmington-Charlotte rail service, utilizing CSX’s existing Charlotte ramp (a facility already supported by volume from other locations). The new “Queen City Express” will commence in September. This will be Wilmington’s first intermodal service in 30 years. Initially, the service will run one train each direction per week.

City of Shafter, CA

Shafter, just north of Bakersfield, CA (150 miles from the Ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach and 260 miles from the Port of Oakland), set out in the early 2000s to establish itself as an inland port to help circumvent congestion and delays at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. The “California Integrated Logistics Center” concept aimed to persuade shippers to route goods via the Port of Oakland (less heavily utilized than the Southern California ports), connected to Bakersfield by main line rail along both the Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF). Shafter also enjoys ready access to I-5, the main north-south interstate in California.

While the city has indeed had some success attracting distribution activities, these achievements were not immediate and have most notably occurred in the last few years (2013-2015). But Shafter persevered through the lean times, investing in infrastructure including 10,000 feet of rail track owned by the city and a 25-mile fiber-optic backbone. In May 2015, Mayor Cathy Prout could point with satisfaction to the fact that 6,000 jobs had been created in the past six years associated with the Paramount Logistics Park, mostly in retail distribution. However, a railroad-owned intermodal ramp has not been established, nor any scheduled intermodal service.

Range of inland ports development underway

A range of projects are being developed around the country, and are at various stages in their life cycles. On the one hand, additional facilities continue to open in AllianceTexas to serve the growing Dallas-Fort Worth market and leverage the critical mass of logistics talent and services. At the same time, new projects are being launched, such as South Carolina’s proposed second inland port, in Dillon, seeking to replicate the success of the Greer inland port.

Another example in the planning stage is the Appalachian Regional Port in Chatsworth, GA (between Chattanooga and Atlanta) being developed by the Georgia Ports Authority (GPA), Murray County and CSX. Plans were announced in July 2015 and bids are out for construction as of July 2016.

How does the Chatsworth plan stack up? Many of the key factors for success appear to be met:

- Projected demand: About 40,000 container loads annually

- Anchor shippers: VW plant in Chattanooga, car parts manufacturers, carpet and flooring producers in northwest GA and eastern TN

- Rail mainline: CSX (Savannah to Atlanta; Atlanta to Chattanooga/Nashville line)

- Distance to port: Approximately 388 miles by rail from Savannah

- Access to interstate highways: Close to I-75, not far from I-59

- Traffic congestion: Planners see opportunity to remove truck traffic transiting metro Atlanta

- Adequate space: 42-acre site on former cattle pasture with a 50,000 container capacity (and a 10-year plan to double capacity)

- Container volume at the coastal port: Garden City Terminal, served by on-dock rail, handles the vast majority of Savannah’s containers

- Over-reliance on truck at the port: About 80% of export traffic inbound to Savannah is via truck

- Political support: Combined support by Georgia Governor Nathan Deal, the Murray County Commissioner and the Northwest Georgia Regional Commission

- Public-private partnership: Plan jointly announced by the Governor, County Commissioner and senior CSX officials. Volkswagen officials were at the kickoff ceremony. Cost-sharing: $24 million to be split by the state ($10M), GPA ($7.5M), CSX ($5.5M) and Murray County ($1M).

At the time of the announcement, the facility opening was projected to take place in 2018. Time will tell if the Appalachian Regional Port will be a long-term success, but the initial prognosis seems favorable. One uncertainty is how VW’s market share will evolve in light of the recent emissions scandal, and the impact, if any, on projected demand at the inland port. There are also neighborhood groups that have raised concerns about environmental and quality of life issues, arguing that Atlanta will benefit at their expense, and these concerns will need to be addressed.

Distilling inland ports factors for success

What advice can we provide to communities or developers seeking to create an inland port? Certain aspects are common to any industrial development but others are specific to the multimodal transportation role played by a landlocked hub. Here is a checklist of ten key success factors to consider during the planning of a new or expanded intermodal logistics hub.

- Demand. Can volumes reach 10,000-20,000+ lifts per year? Who are the anchor shippers?

Objective assessment of projected traffic volumes to/from the service area is a key step in the evaluation process. Specific industries, products, origins and destinations should be identified. Anchor shippers are essential. Analysis must be fact-based and compelling – demonstrating sufficient volumes to amortize facility costs. Projected demand should reach 20,000 to 50,000 annual intermodal lifts for a greenfield destination facility, although lower volumes of 10,000-30,000 could be viable if the facility is along a route to another location to be served by rail. - Port link. Are there close ties with a successful ocean container port, 200+ miles away?

A link with a successful ocean container port is crucial to success, if international container flows are a key part of demand. Distance to the seaport should not be much less than 200 miles, to ensure that rail transit can be cost-competitive with truck. High container volumes at the port and on-dock rail are advantages for an inland terminal. - Site. 40+ acres for intermodal ramp, more for distribution facilities, near good highway access?

Open acreage, utilities and easy connections to good state or interstate highways are essential. A facility is best situated away from residential uses (noise, air emissions concerns). About 40 acres would be the minimum size for an intermodal terminal, with adequate space for nearby distribution facilities adding further to the site requirements. Adequate water, sewer, electricity and access roads are required. - Rail. Situated on or near a mainline intermodal rail route, attractive to a Class I railroad?

The proposed site must lie on or near a mainline intermodal rail route. One or even two Class I railroads must be attracted to the project to develop and help champion the intermodal facility that lies at the heart of an inland port. A railroad’s interest will be directly linked to current and future intermodal volumes (first point above). Intermodal is currently the number one source of freight revenue for Class I railroads, so the railroads are keenly interested in these opportunities. Railroads will be most attracted to a location that could allow smooth operations – quick on and off the mainline without causing congestion, and easy set-off and pick-ups of blocks of cars if the facility is not the final destination on the route. - Cost. Competitive land, improvements, road links, operating costs, and taxes?

Cost-effective capital investments and ongoing operations are important. Inland ports operate in a competitive environment and need to keep costs under control. Taxes can vary by state and municipality, and figure prominently in a location decision – this can be particularly true for businesses siting facilities subsequent to the establishment of the intermodal ramp. - Labor. Access to a skilled, hardworking labor force?

Effective and efficient workers are essential, to staff the transportation and logistics facilities. Some of the types of jobs created at an intermodal ramp are lift operators, hostler drivers, gate operators, load planners, and mechanics. Further development of related distribution operations creates a variety of material handling jobs, with attendant customer service reps, salespersons, inventory managers, etc. Staffing these positions can be a challenge, since available land may be a long commute from population centers. - Business case. Value proposition that is attractive to a developer, railroad and tenants?

A business case should be constructed for specific high-potential industry, product and origin-destination uses, demonstrating the superior economics of the proposed logistics site. In addition to transferring containers from rail to truck and vice versa, the core intermodal facility may be designed to act as a storage yard of loaded or empty containers for anchor shippers that would value that service. - Environmental benefits. Can it replace truck with rail traffic, attractive in a congested region?

Conversions of truck to rail traffic result in fewer greenhouse gas emissions. If the seaport area and/or seaport-inland route are heavily congested, these benefits are amplified. - Public support. Is there active involvement by local officials and support from the public?

Active involvement of local, regional and state officials is crucial to overcoming various constraints (e.g., zoning, infrastructure, and training) and obtaining enabling grants and tax incentives. Local public support is also essential, as concerns about traffic congestion, emissions, and noise can evolve into concerted opposition if perceived local benefits don’t outweigh them. - Collaborative effort. Is strong leadership in place, with effective public-private collaboration?

Assembling a great team to plan and execute an inland port project is crucial. The right leadership must be found and an effective collaboration established. All successful inland ports have involved extensive public-private cooperation.

Inland ports continue to draw interest from municipalities, shippers and developers. They offer an efficient link to global markets via intermodal rail service and coastal container shipping hubs, and have delivered major economic benefits to inland regions. Where projected traffic warrants the investment, inland terminals and distribution facilities can be a win-win for both private and public sector constituencies. Heeding our ten-point checklist will help ensure success.

* * * * *

Contact us to explore how we can support your strategic, operational, and investment needs: info@newharborllc.com

Tom Keane is a Principal at New Harbor Consultants, a management consulting firm located near Boston. He helps clients translate their vision into practical results through fact-based analysis and clearly conveyed insight. Tom brings 25 years of experience across a range of industries, including transportation, logistics, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing. Projects focus on acquisitions, strategic direction, market positioning, operational improvement and hands-on implementation.