Supply-demand balancing – optimally and consistently – is tough for many mid-sized companies. Even the largest corporations can make mistakes. What are some practical suggestions to tackle these challenges?

The art and science of aligning supply and demand is as old as commerce itself. The processes involved in this activity today are known by several names: Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP); Sales, Inventory and Operations Planning (SIOP); and Integrated Business Planning (IBP). By any name, though, the goal is to harness planning and real-time information to adjust supply or demand, set inventory policies, allocate available products and resources, and ultimately maximize both customer satisfaction and company profitability.

What’s at stake?

The kinds of things that can go wrong include:

- Customer service mismatches. Not all customers are equal, in terms of cost to serve and profitability. Without setting customer segment-specific service levels and incentives, it’s hard to optimize the supply-demand balance.

- Demand side issues. Forecasts can be too high or low, particularly for new product introductions or style-sensitive items. If demand is unexpectedly high, irate customers and lost sales can result. It’s a painful but all-too-common occurrence.

- Supply side challenges. Any element of the supply chain or network can turn into a bottleneck that creates shortages. This can occur in the upstream components required as inputs to product manufacturing; at the plant level due to capacity or flexibility limitations; or within the downstream finished goods distribution system.

- Inventory mismatches. Inventory – at the raw materials, intermediate, and/or finished goods levels – serves as the essential buffer between demand and supply, given the fundamental uncertainties involved. However, many companies are saddled simultaneously with shortages of key inputs and products and too much of the slow movers and obsoletes.

Here are examples – presenting issues, as a doctor would say – drawn from our experience:

- Industrial supplies: Unexpected elephant orders causing sharp drops in service levels for all customers. We’ve seen order fulfillment at distribution centers drop from 95% to 60% with very little notice.

- Consumer tech: Inability to rationally allocate hot new products, in case of shortages. Resulted in lost sales, dysfunctional intra-company competition and unhappy resellers.

- Food manufacturer: Overly complex supply chain, using more than 1,000 warehouses to reach US retail customers. Company scored worse than any other supplier in the retailers’ ratings.

- Beverage maker: Company was able to provide a set of beautiful S&OP process maps. Unfortunately, production leaders did not believe the demand forecast, so routinely ignored it.

- Building products: Intense supply-demand planning process, but not organized to make the right decisions at the right time by the right people.

- Fashion: Pre-season buys and store push allocations are notoriously hard to get right. This supply-demand team lacked timely information and agile decision processes, leading to excessive markdowns.

In brief, no company is immune to these issues. They can occur in make-to-order businesses as well as for make-to-stock, in B2B companies as well as in B2C enterprises. And these issues are global in nature.

Where is your company on the journey to excellence?

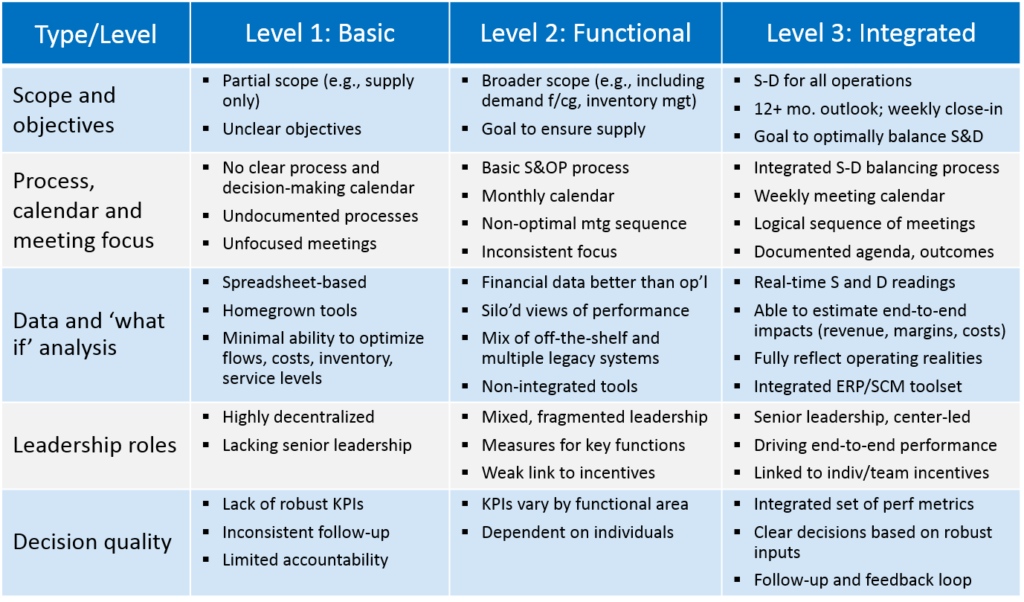

Mid-sized manufacturers generally have elements of a supply-demand balancing process in place. But they often lack the key integrating elements that produce real value. We posit a maturity framework against which you can assess your company’s level of development, with five main dimensions and three maturity levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Supply-demand balancing maturity model

What do we suggest?

Start with practical steps on information and tools, process steps and roles (Figure 2).

- Facts: Supporting data, analyses and tools

- Process: Objectives, sequence, frequency and outcomes

- People: Decision-making roles in the process

Figure 2. Three-pronged approach

Essential data and analytics

For mid-sized companies, the starting point must be robust data and analysis. The sorts of information needed to support supply-demand balancing includes:

- Customers/Markets:

- Actual demand: Recent and current, actual vs plan, why different, mix changes

- Future demand: Outlook/anticipated demand and basis of shifts, forecast error

- Performance: Fill rates, lead-times, delivery date reliability

- Orderbook: Orders on hand/backlog status as future demand indicator

- Macro inputs: GDP and sector/geo-specific indicators, actual and forecast

- Micro inputs: Collaboration-based customer forecasts

- Operations:

- Bills of materials, substitution rules, replenishment lead times, allocation rules

- Plants, DCs: Capacity utilization, product trends, overtime, constraints, planned outages

- External supplier materials, capacity

- Financials:

- Dollarized data: Sales, operating costs, gross profit, inventory

- Trends and mix: Past, present and outlook

With this data, typically found in a company’s ERP or supply chain management (SCM) systems, planners can construct models targeting specific aspects of supply-demand balancing. These include:

- Network cost model, with ability to test short-term changes. Optimizer functions (available, for instance, as add-ins to Microsoft Excel) can provide the ability to quantify ‘what if’ effects of shifting a supply source to meet evolving demand.

- Demand outlook incorporating new products, complexity levels and large orders. Forecasts can be adjusted using complexity factors, for instance, to properly reflect the challenge of producing more sophisticated product lines.

- Dollarization of lost revenues (and margin) and delta to optimal, current and trend. Quantifying opportunity cost is key to rational decision making and needs to be incorporated in the analysis of alternative supply-demand solutions.

- Improved inventory management and statistical/discrete integrated forecasting tools. Mid-sized companies should review their inventory planning tools to ensure they are using up-to-date parameters, applying the best statistical techniques and building in the effects of specific large orders.

Many S&OP software solutions exist. These range from supply-demand planning modules within a broad suite of supply chain software to ‘best-of-breed’ solutions for S&OP or IBP. But they may not be the answer, in our experience. For a medium-sized manufacturer, it can be better to build models internally that address company-specific issues, such as those mentioned above.

Then, once processes are refined and initial benefits realized, the supply chain planning team may wish to investigate more sophisticated third-party software solutions, self-funding them with the gains realized.

A process that works

Three kinds of meetings or conference calls need to be organized – to address supply, demand and supply-demand balancing. The focus needs to be on the critical decisions, building up the essential information in a structured sequence to inform the optimal resolution of conflicting objectives. The exact process that’s best will vary but we can outline what a successful process looks like.

On supply review calls, questions focus on plant capacity utilization, availability of long lead-time components, planned plant downtime, transport delays and inventory levels. These should be convened weekly. Participants may include operations (SCM), plant and DC managers and S&OP team members.

For demand review calls (which may be done separately by business line or sales channel), topics are recent sales trends, individual large orders, new product introductions, shortages of finished goods, delivery performance, product sunsetting, backorders, customer complaints, competitive intelligence, industry demand factors and macro trends. A prerequisite, on the demand side, is that customer service levels are well designed and aligned with customers’ expectations and willingness to pay. These calls should occur weekly or every other week. Participants may include sales, marketing, demand forecasting, finance and S&OP team members.

The supply-demand balancing calls conduct the essential adjustments and allocations needed to best meet all constraints and objectives. These calls should be weekly or every other week, timed to take place shortly after the supply reviews. Business owners and S&OP leadership should participate.

Critical to success is asking the right questions, building a shared view of the ‘truth’ based on facts, and addressing issues in the right sequence and at the right pace. Key questions on the balancing calls can include:

- How are we doing, externally for customers and internally for Operations and Finance?

- How are things changing, on the Demand and Supply side?

- What will likely change further, in the short term?

- Where are we/will we be most out of balance?

- What are the major risks and opportunities?

- What are the main options to adjust, in the short term?

- What are the tradeoffs, based on robust analysis?

- What course of action is recommended?

The right people making the right decisions

An oft-observed problem is that the right people are not ‘at the table’ making well balanced, fact-based decisions on a timely basis. This may be because the supply-demand balancing process has been delegated too far down the organization, or is too siloed, to gain the broad, senior-level attention needed. Or it can simply be due to the wrong sequencing of decisions.

For instance, we have observed situations where essential allocation decisions were made by plant managers on the supply call, without consideration of the longer-term impact on key customers. In another situation, we recommended that the division CEO lead critical calls – this had a most salutary effect on aligning sales, manufacturing and distribution executives. Other problems can arise from decisions made without the full facts – decisions that are subsequently difficult to reverse.

Who should lead each type of call? For the supply reviews, we suggest that the VP of Operations (or equivalent) chair the meeting. On the demand reviews, generally a Business or Sales VP would be in charge. And for the balancing calls, senior leadership is required – CEO, COO or Supply Chain VP level – to make the tough decisions and ensure that actions are taken.

Typical decisions made at the supply-demand balancing meetings include:

- Switching a customer from one plant or DC to another, to meet short-term constraints

- Increasing or reducing the use of overtime or temps at plants or DCs

- Substituting a more-expensive but available component for an out-of-stock BOM item

- Air-freighting product to meet committed delivery dates

- Filling some customers’ orders completely and on time but not others

- Changing promised lead times to certain customers, per allocation rules

Concluding thoughts on supply-demand balancing

Companies constantly struggle to achieve the ideal balance of supply and demand. Many mid-sized manufacturers or brands have not yet attained the mix of process, people and underlying fact base needed to deliver both customer satisfaction and lean, profitable operations. Conducting an objective appraisal of the current state of supply-demand balancing, missed opportunities and potential improvements can offer an attractive payback. The maturity framework presented can help benchmark existing practices. Enhancements to analytics, process and decision-making are eminently doable. In our experience, the results are compelling in terms of customer satisfaction, profitability and management effectiveness.

* * * * *

Contact us to explore how we can support your strategic, operational, and investment needs: info@newharborllc.com

David Bovet is the Managing Partner of New Harbor Consultants, a management consulting firm located near Boston. He focuses on helping clients translate their vision into practical results. David brings 30 years of experience across a range of industries, from manufacturing to transportation and financial services. Projects focus on strategic direction, market positioning, operational improvement and hands-on implementation.