Irrational consumers or unresponsive supply chains?

Consumer behavior is not necessarily irrational. Applying business inventory management techniques to toilet paper purchasing at the household level highlights three rational considerations: Higher home demand due to reduced usage at work or school; perceived increased safety/emotional risk of each buying occasion at the store; and a higher safety stock as resupply uncertainty skyrockets. Combined with relatively inelastic supply from US factories, the result has been widespread product shortages. Restoring balance will take time.

* * * * *

Toilet paper is the signature shortage in the early weeks of the coronavirus crisis. Almost all Americans are familiar with the sad sight of empty shelves at the supermarket, where formerly mountains of white paper, neatly packaged in plastic, held sway. The abundance of choice has been transformed into a hunt for the elusive article.

Why is this? Is the lack of stock due to panicked consumer buying? Is there some systemic flaw in the nation’s supply chain for this essential item? How will supply finally catch up with demand? We tackle these mundane but essential questions below.

Consumption spike

As the coronavirus spread silently across the United States, consumers began to fear shortages of vital goods. Among these was toilet paper. Sales during four weeks in March were double what they had been in the prior year. In most stores, as of late March and early April, there was little if any to be found. This shortage is generally ascribed to hoarding behavior by consumers, engendered by fear that supplies will not be available when needed in the future. “There’s a rumor that there will be a shortage of toilet paper-and then there is a shortage of toilet paper,” as John Catsimatidis, owner of New York’s Gristedes chain of supermarkets, put it to the Wall Street Journal. There is no real shortage of toilet paper, he insists. 1/

This behavior is well known by store managers, who observe something similar though on a more local scale in advance of snowstorms and hurricanes. In those cases, the shelf supply of toilet paper is wiped out, but the system can quickly recover. With the novel coronavirus, “the spike in demand is nationwide, has been going on for some time, and is open-ended,” per the Washington Post. The interim president of Giant Food said, “There is not a supply shortage, but it does take some time for the manufacturing process and our supply chain to catch up from the significant spike in demand.” 2/

We also know more about ‘irrational’ behavior from recent research by practitioners like Dan Ariely, Professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University. “I am not surprised,” Prof. Ariely told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in mid-March. “We can’t tell people that this is going to be terrible and then tell them to do nothing.” 3/ Concerns were fed by news streams reporting the spread of the disease and suggesting that those exposed might need to self-quarantine for weeks. With no guidance available, people indulge in overreaction that makes them feel better – control what you can control. “But to buy a year’s supply of toilet paper? That’s nuts,” said Catherine Eckel, director of the Behavioral Economics Program at Texas A&M.

Toilet paper supply chain strains

About 90% of toilet paper sold in US supermarkets is manufactured domestically. As such, this commodity joins others whose low value-to-volume ratio and locally-available raw materials make it cheaper to produce in the US rather than to import from, say, China, with the high logistics costs that would entail.

Among the leading brands is P&G’s Charmin. The company makes toilet paper and other products in Mehoopany, PA – its largest plant in the United States, employing 2,200 people. Mehoopany has added face masks to its output recently. Lately “miles upon miles of tractor trailers” are lined up to load the precious cargo, according to the Pocono Record. 4/ Even this massive production facility cannot keep up with demand.

P&G’s Charmin tissue plant, Mehoopany, PA on the Susquehanna River.

Source: Flickr photo, consulted online April 9, 2020.

One challenge for the toilet paper supply chain is that two distinct distribution channels exist. The first channel is the one we all know as consumers: Consumer product makers, such as P&G, Kimberly-Clark (Scott and Cottonelle brands) and Georgia-Pacific (Quilted Northern), manufacture the product, package it in convenient bar-coded packs of four, six or twelve rolls and distribute from their own distribution centers to the warehouses operated by major retailers, such as Walmart, Target, Kroger or Wegmans. These chains then restock their stores nightly from regional locations. This is the supply chain that has currently come under dramatic strain from panic buying.

The second channel is wholesale distribution that serves offices, restaurants, schools, factories and other locations outside the home. This channel is experiencing a sharp demand decrease during the present stay-at-home regime. Couldn’t we just redirect some of the toilet paper in this channel over to our local supermarket?

It’s not that easy. First, there are differences in quality. Office or industrial paper is not as thick or soft as what we buy for home use and the larger rolls may not fit on home dispensers. Second, the packaging is different: For the consumer channel, a universal product code (UPC label) is printed as a barcode directly on the plastic, so the sale can be scanned at checkout. In the wholesale channel, the product is delivered to an office building, for instance, in pallet or case quantities. These packages do not have bar codes on the smaller packs or individual rolls.

We recently experienced first-hand an example of channel crossover, however. Livi toilet paper (made by Solaris Paper at US plants from Indonesian bulk paper imports) is normally distributed to washrooms in professional buildings, hotels, restaurants and schools. The Livi VPG bath tissue product comes in a format of 96 rolls per case and stacks 24 cases per pallet.

Distribution channel substitution: A wholesale roll sold in unit quantities at a specialty neighborhood market in Cambridge, Mass., observed April 9, 2020.

One of our partners was able to find a dozen rolls of this toilet paper, sold as individual items, in a premium local shop – when the nearby supermarket was totally out of stock. Notably, there was no UPC code on the roll, so it had to be priced manually at checkout. At $1.49 per roll, this product was more expensive than Walmart’s online offer of Charmin 12-pack for the equivalent of $1.08 per roll – but revealed on its website to be out of stock.

There are other real challenges in the supply chain. Some US toilet paper manufacturing plants routinely operate round-the-clock shifts to optimize equipment usage, so it is not easy to increase output in response to sudden spike in demand. Truckers, even though they are socially isolated in their vehicles, still need to eat and use restrooms. With the aging demographic of US drivers, there is some legitimate concern that drivers could be in short supply – though groceries are considered essential and the reduction in other product sales should create some slack.

Finally, at the stores themselves there are issues. At the Gristedes supermarkets and many others, employees wear masks, are protected by a plastic screen and customers are kept six feet apart. Still, parents of teenagers working at a local supermarket in my area, concerned over the exposure of their children, are keeping them home from their checkout jobs. Such health concerns are very legitimate and rational; recent reports have noted deaths from COVID-19 among grocery workers.

Household buying and stocking of toilet paper

Some part of consumers’ behavior can also be viewed as entirely rational. This arises in two ways. If we apply the business concepts of inventory management to the household, it’s clear that the dramatic recent changes in lived reality could legitimately drive sharp changes in buying and stocking toilet paper.

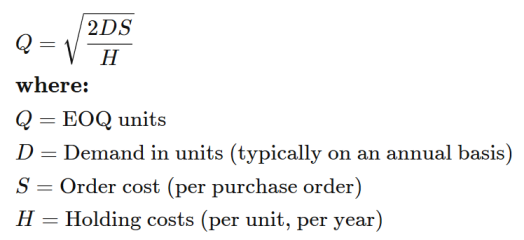

First, let’s consider cycle stock and the economic order quantity. The classic calculation is based on demand, cost to order (or buy at a store) and holding costs a/. For toilet paper, the household’s demand may be up, since lockdown prevents us from spending the day at the office or school. The ‘order cost’ may also be substantially higher, in the sense that the shopping experience has drastically changed. The perceived health risk, stress and anxiety from shopping at the grocery store has changed what used to be a mildly pleasurable experience into a grim necessity. Thus, the effective emotional cost of the purchasing occasion is up sharply. The holding costs, meanwhile, for many households are very low, especially for products with long shelf life, like toilet paper.

One can make a variety of assumptions about specific inputs to a ‘household inventory’ calculation. But the implications hold across a wide range of conditions. If we assume, for instance, that demand rises for the average household by just 75% (due to staying home from work or school all day) but that order cost (emotional anxiety of shopping) increases by 100 times (while holding costs are unchanged), the quantity to be purchased during each visit to the store goes up by a factor of about 13. Thus, an average purchase of 2 rolls, for example, mushrooms to 26. This will also be consistent with fewer visits to the store.

But that’s not all. The second concept to be considered from inventory theory is safety stock b/. This means, beyond the normal cyclical replenishment of stocks, what extra inventory do we need to protect ourselves against unexpected variations in usage and in resupply lead time?

In normal times, for a common consumer item like toilet paper, the deviation as we consumers experience it at the grocery store is essentially zero – it’s always there. And our usage is consistent. So, we do not need any safety stock, as long as we live not far from a store.

In pandemic times, however, we experience ourselves (and see even earlier on television) that stocks of toilet paper on the shelf at the store have suddenly disappeared. Lead time has become extremely long and variable, seemingly overnight. This is the key variable – if we now expect an average lead time of say, three weeks to replenish our supply from the grocery (fewer trips to the store), with a standard deviation of two weeks due to uncertain store stocking, we have to cover ourselves for 5 weeks just to reach one standard deviation above the mean lead time. And typical inventory service levels for critical items cover a higher proportion of possible outcomes than just one standard deviation – say, 98% of possible outcomes. That would equate to about 10 weeks, to be safe. Factoring in a 75% increased usage from being home 24/7, and the safety stock calculates out at 43 rolls. One could assume less or more than 75% increased usage due to working from home, but you get the idea.

Thus, very quickly, each household would like to purchase 26 rolls of cycle stock and initially seeks to build a safety stock of 43 rolls in addition, given plausible assumptions. This translates to a one-time hit on the store of 67 additional rolls per household (26 + 43 – 2), more than five 12-packs of toilet paper. And more than 30 times normal. These figures remain surprisingly large even as one reduces the lead time assumptions. It’s understandable, then, that both initially, and until consumers see the stock returning to the shelves, people will buy many times what they normally would – if they can find the product – regardless of their actual use. This gives an idea of why demand spiked in March.

The shortage will last until either (a) suppliers can squeeze out more production, (b) enough product can be converted from wholesale channels, (c) consumers reach their new preferred inventory levels or (d) shoppers see product on the shelves and decide the shortage has passed. This could take some weeks. When the tipping point is reached, the crisis will likely end as quickly as it began.

Lessons learned

While we hope for the end of current shortages and lockdown conditions, it’s prudent to plan for more disruptions in the future. Whether due to climate change, pandemics, earthquakes or other existential threat, better plans and behaviors are in order at household, enterprise and government levels.

Consumers

- The outlook: Shortages will probably drop away quickly once retailers and manufacturers adjust their supply chains.

- For shelf-stable items: Stock for more than just a few days; then monitor your inventory.

- Be prepared. Consult FEMA and local government advice for risks specific to your area.

- Buying trend: Online ordering of bulky basics for home delivery will likely increase permanently.

- Consider the environment. Virgin paper products are more resource-intensive than toilet paper made from recycled paper. Or switch away from paper entirely: What about a bidet instead?

Companies

- Prepare for predictable surprises. Contingency planning should address a wide range of threats.

- Arrange flexible supply options. From sourcing to distribution, ensure alternatives are in place.

- Response teams: Create operations and communications teams that can swing into action fast.

Governments

- Contingency planning: Consider major threats and develop crisis plans to address each.

- Existential action: Use COVID-19 as a wake-up call to address climate and the environment.

- In the US, a more coordinated federal – state – local approach is needed.

References:

- A coronavirus bull market for groceries. Tunku Varadarajan, The Wall Street Journal, April 3, 2020.

- Flushing out the true cause of the global toilet paper shortage amid coronavirus pandemic. Marc Fisher, The Washington Post, April 7, 2020.

- Panic-buying a natural reaction to uncertainty, behavioral experts say. Michael E. Kanell, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 14, 2020.

- Need toilet paper? Procter & Gamble plant goes into overdrive during coronavirus crisis. Kathryne Rubright, The Pocono Record, March 30, 2020.

Technical notes:

- Economic order quantity for cycle stock formula:

- Safety stock formula, for lead time variability only:

Safety stock = Z * average use * lead time standard deviation, where Z is the service level factor

Example safety stock estimate = 2.05 * 10.5 * 2 = 43 rolls, where:

2.05 is the service factor for 98% availability

10.5 (2 rolls per week x 175% x 3-week avg lead time) is the average use over lead time

2 weeks is the standard deviation of lead time

* * * * *

Contact us to explore how we can support your strategic, operational and investment needs: info@newharborllc.com.

David Bovet is the Managing Partner at New Harbor Consultants. He focuses on helping clients translate their supply chain vision into practical results. David brings 30 years of experience across a range of industries and geographies. Projects focus on strategic direction, operational improvement and hands-on implementation. He is the co-author of Value Nets: Breaking the Supply Chain to Unlock Hidden Profits, about the power of fast and flexible logistics-intensive business models.