Stay-at-home orders in the time of coronavirus have dramatically altered the path food takes from farm to plate. Grocery stores have suffered shortages while farmers plow crops under due to lack of demand from the food service channel. What is happening to our food chain? And from this chaos, which shifts in the food supply chain will live on once the pandemic ends? In this Brief, we bring out our crystal ball and share our educated guesses.

Five enduring trends we see from the pandemic: (1) more online ordering for home delivery, (2) growing local food solutions, (3) automation in processing plants and stores, (4) de-risking the supply chain and (5) new business models.

How the food supply chain is changing

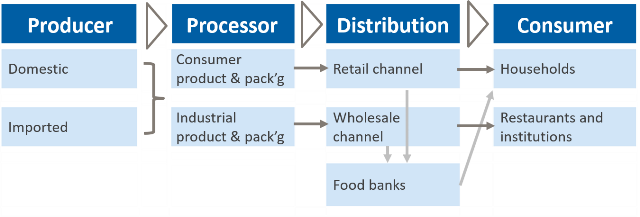

The coronavirus has upended several longstanding patterns in the food distribution ecosystem. New flows are blossoming and the trend toward online ordering and home delivery are accelerating. The pandemic has driven changes in all areas of the food supply chain, from production to consumption. We will show in this Brief how the normal flows in the US supply chain are evolving from the pre-crisis situation shown below to a more complex pattern.

US food supply chain – traditional flows

Consumption of food

Food consumption in the United States is vast: We spent more than a trillion dollars on food and beverages in 2019. Roughly half of our food is consumed at home, with the other half normally eaten at work, at school or in restaurants. Yet food takes up a declining share of the consumer’s dollar. In 2019, consumer spending on food eaten at home made up just 6% of total outlays, down from 7% in 2002. In addition, consumers spent another 1% on alcoholic drinks for home use and 5% at restaurants.

The pandemic is dramatically changing consumption patterns. Home use is up sharply, since dining at restaurants, schools and offices is down about 80%, as of this writing. The demand for consumer staples is spiking, especially for shelf-stable or frozen items. And how households obtain their food is changing as well.

In the face of closures, stay-at-home orders and social distancing, shoppers who do venture out to the store are buying in record quantities. For the week ending March 18, grocery sales were up by 79% over the prior year. 1/ Demand has been particularly strong for the staples: Pasta, rice, flour, dried beans and canned goods. Sales of processed comfort foods, like Chef Boyardee and Campbell’s soup, have skyrocketed, reversing at least temporarily a longstanding trend toward healthier fresh and organic foods.

Grocery chain stores have been plagued by shortages. Recent visits have revealed empty shelves for flour, beans and butter – along with paper goods such as toilet paper and paper towels. Yet smaller local shops have flourished during the pandemic. “We have not run out of anything significant, “ Jim Wilson, owner of Wilson Farm in Lexington, Mass., told me recently. “We’re nimble,” he added. “It’s being in the right place at the right time” to source successfully in these challenging times.

Plentiful produce at a family-owned farm stand

And online ordering is up. Instacart reports an order volume growth of more than 150% for grocery home deliveries in the early weeks of March versus the prior year, as well as a 15% increase in average basket size. The company announced plans (in late March) to bring on 300,000 more personal shoppers in the next three months. Business is also booming for other home delivery services such as FreshDirect, Shipt, Mercato, Peapod and Amazon’s Prime Now. The challenge lately for the consumer has been snagging a delivery date – waiting weeks for delivery has become common. Instacart reported their business had quadrupled, as of mid-April. And the time required for the personal shopper to pick the order at the store has mushroomed. As a result, the online promise of instant gratification is not yet being fully realized. 2/

The explosion of online grocery shopping reflects the closure of restaurants, schools, businesses and malls. Households normally spend 54% of their food budget away from home. 3/ But restaurant sales were down by more than 65% in the last two weeks of March, according to Black Box Intelligence data from 50,000 eateries. Nearly all schools in the United States are closed, as of April – impacting breakfast and lunch programs that feed millions of children. Offices and shopping malls are closed.

Retailers and restaurants are launching interesting hybrid solutions for these exceptional times. Specialty shops, from farm stands to wine stores, have added essentials such as toilet paper and hand sanitizer. At Wilson Farm, toilet paper sourced from the wholesale channel is on sale. The rolls are not the standard consumer item – the brand is not well recognized and the packaging, by the individual roll, does not bear a UPC bar code. But to a delighted patron, the sight of toilet paper on sale was a welcome relief.

Industrial channel toilet paper alongside the strawberries at a local farm stand

Wholesale channel toilet paper and napkins on sale at Wilson Farm, Lexington, MA. Author photo April 23, 2020.

Restaurants, from nationwide chains to local venues, are adding items aimed at home consumption. Panera Bread, for example, is offering a new service to provide customers with milk, bread and fresh produce as well as soups and sandwiches via the chain’s app, for contactless delivery, pickup or drive thru. California Pizza Kitchen launched CPK Market, a new platform for specialty meal kits for consumers. Local restaurants, such as 80 Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts now offer phone ordering and handoff directly to your car trunk.

Restaurant chain offering for home consumption

California Pizza Kitchen’s new meal kit solutions for the home. Source: Food Business News, April 2020.

We have shown, by translating standard product inventory management formulas into household shopper terms, that shoppers are not necessarily irrational when they buy far more than usual. Yes, there is an emotional pull toward trying to control home stocks of a specific item like toilet paper or beans, in the face of so much uncertainty. But consumers are also logically driven by dramatically greater uncertainty of supply, desire to limit the number of visits to the store and higher home consumption with restaurants closed. 4/ This behavior will continue until the retail channel can be fully supplied by growers and manufacturers, sufficient product can be diverted from the now-sluggish wholesale channel, consumers reach their desired levels of cycle and safety stock or availability convinces shoppers to reduce buying and destock their pantries.

Production challenges

Overall, some 90% of American food consumption is supplied domestically. 5/ This share varies greatly, however, by specific foodstuff. Tropical crops are largely imported into the United States. Think coconuts, pineapples, bananas, cocoa and coffee. During the US wintertime, a wide range of fruits and vegetables are imported from the Southern Hemisphere, such as blueberries and green beans. Indeed, US food imports grew by about 3.5% per year in volume, from 2000 to 2018 before slowing to -1.0% in 2019 during the tariff wars. With international air passenger traffic now down by more than 90%, air freight capacity and rates are an issue. Global air transport of food in March (fish, fruits & vegetables and flowers) fell by 40% to 60% from the first week to the last week of the month. In general, though, the lengthy global supply chains that are constraining availability of items such as consumer electronics and imported automobiles are not fundamentally impairing our food supply.

US food production originates heavily in California, the Midwest, Texas and Florida. Harvested fruits, vegetables and meat move via processing facilities to major retail and wholesale distribution centers to feed the nation’s consumers, heavily concentrated in the cities. An efficient system of plants, transportation (truck and rail) and warehousing assures a speedy flow of goods in normal times.

Outbound food flows by county

Outbound moves by county, 2012. Highest volume flows in darkest color. Exponential scale. Source: Food flows between counties in the US, Environmental Research Letters, by Lin, Ruess, Marston and Konar, July 2019.

In this pandemic time, production is strained in several ways. This industry has evolved to an efficient yet highly concentrated system, making meat processing a potential weak point in the food chain: The share of hogs slaughtered in huge plants processing more than one million animals per year rose from 38% in 1977 to about 90% today. Meat plants also involve shoulder-to-shoulder workers on the processing lines to prepare various cuts. These workers have experienced surges of illness. More than a dozen plants have reduced output or closed, as of April 18th, according to The New York Times. 6/ Prominent among these are the Smithfield Foods pork processing plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, which closed indefinitely on April 12th after more than 600 workers tested positive for the virus. This plant alone produced 5% of the nation’s pork. Cargill’s pork and beef plant in Hazleton, PA, normally employing 900 people, is another example. As of April 26th, more major pork plants had closed (including a JBS plant in Minnesota and a Tyson Foods plant in Iowa, in addition to the Smithfield plant), representing nearly one-third of the US pork supply. A large beef processor in Washington state closed on April 23rd. Cold storage facilities in the US hold about two weeks of supply and plants that are closed for the virus are generally down for two weeks. So the chance of a US meat shortage is quite real. On the other hand, the Sanderson Farms poultry plant in Laurel, MS, recently reported that 152 employees had recovered from the virus and returned to work; operations continue there.

One of the most shocking stories from the food production side is the destruction of surplus crops at the farm. This is primarily due to the sharp downturn in demand via the wholesale channel. Milk producers are faced with dramatic declines in consumption due to school and restaurant closures. With no ability to store or freeze the product, surplus milk has been dumped. Vegetables ready for market have been buried in farm fields. The sudden downdraft in the wholesale channel cannot, for many producers, be quickly compensated by a shift to the high-demand retail channel.

Ripe crops being buried on the farm

A field of onions waiting to be buried, in Idaho. Source: Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic, by Yaffe-Bellany and Corkery, The New York Times, April 11, 2020.

Another concern on the growing side relates to the health of migrant workers, essential to the harvesting of everything from lettuce to cherries. Planting is a highly mechanized operation in which one farmer, sitting alone in the cab of a high-tech tractor, can plant 1,000 acres of corn in a day. 7/ But harvesting and packing fruits and vegetables requires a large contingent of field labor that moves around the country as different crops ripen. This work force, heavily immigrants, typically travels in groups and lives in cramped quarters near the fields. They are deemed ‘essential’ but their working and living conditions make social distancing and self-isolation nearly impossible.

Trucking is another possible – but not in our view major – concern. Trucks move about two-thirds of all US freight by value and truck drivers are indeed essential workers. While drivers generally operate alone in their cabs, the availability of meals and restrooms has posed an issue, as well as the toll of virus-induced illness among drivers. Driver turnover is down during the pandemic, as drivers seek to stay with their current employer in this time of uncertainty. And many drivers report a newfound pride in their work – just like food factory workers – as they strive to keep the country supplied during the pandemic. Demand for commercial truck transportation is down – by about 20% on most US lanes, in mid-April, based on number of trips relative to normal activity. By type of activity, trucking to grocery stores was down about 10% whereas non-grocery trucking was down by roughly 30%. 8/ So the collapse of demand in other sectors has freed up capacity for the grocery supply chain.

Despite these legitimate concerns, we generally do not believe that American consumers face a broad threat of food shortage from domestic production. The mix of large, well-organized national producers and local seasonal growers should suffice to keep food flowing to American tables. The exception may be temporary shortages of pork and other meat, due to the shutdown of large plants that have experienced high levels of illness. This overall outlook presumes, of course, rational safety measures for COVID-19 containment across the supply chain over the necessary time period.

A nice success story comes from King’s Hawaiian, the industrial baker of rolls and bread sold in grocery stores across the United States. The company has kept store shelves stocked – in the face of demand that has soared 20%-30% above normal. King’s Hawaiian is used to peak demand spikes around holidays such as Thanksgiving and Christmas. Their network of plants and cold storage facilities can absorb seasonal ups and downs. By reducing the number of items offered to eliminate the most labor-intensive products, adding back some unused capacity and following health protocols, King’s Hawaiian has maintained 99% fill rates to its retail customers. At the same time, the company has benefited from the demand shift from food service to retail with respect to its raw material usage. Availability has increased for dairy and egg products within industrial use-designated supply chains, allowing the company to extend volume and price certainty. However, these same commodities in retail consumer form, such as table eggs and milk in gallon or half-gallon jugs, flow via separate and distinct supply chains that have been strained by the increased retail demand. 9/

King’s Hawaiian product display

Distribution channels and crossover

Food distribution channels are straightforward, in normal times. The retail channel serves consumers who shop at supermarkets and local purveyors. The wholesale (food service or industrial) channel delivers food to restaurants, schools, company cafeterias, hospitals, hotels and factories. In addition, food banks serve those in need, drawn from the surplus in these two channels. Networks of distribution facilities across the country are linked to efficiently support very high product availability for consumer goods such as food, in normal times.

Product availability at supermarkets has been variable during the pandemic. In part, this is because the large retailers have successfully pressured manufacturers, over the past several decades, to hold the inventory in the supply chain – allowing them to operate in a just-in-time fashion. Retailers have been able to slash their inventories. At a crisis time, however, they lack the extra stock to fill skyrocketing demand. Some store chains have experienced case fill rates of 50%-60%, from their own distribution centers to their stores – when normal replenishment rates would be in the high 90s. This despite, in many cases, good performance by the manufacturers.

Online ordering for home delivery or pickup of groceries is a major theme of the pandemic. The online grocery market, at 2% of total food and beverage sales in 2019, exhibited the lowest ecommerce penetration of any product category prior to the virus. Computer and consumer electronics, for example, recorded 39% of sales via ecommerce in 2019 and apparel stood at 26%. Yet even prior to the COVID-19 crisis, food and beverage sales were projected to be the fastest-growing product category online. Amazon represented the largest share of grocery ecommerce sales in 2019, followed by Walmart, Target and Kroger. 10/ Clearly, the pandemic is turbocharging grocery online penetration. The young urbanites clicking from their kitchen table have now been joined by suburban octogenarians who are surprisingly agile with a mouse. Growth at present is more constrained by labor shortages for picking and delivery than it is by product outages.

Groceries are not easily diverted from one channel to another, because of: (a) product quality differences, (b) unit size differences, (c) lack of barcoding, (d) different plants and (e) separate distribution channels. Sourcing, packaging and contracting all must be performed to identify and onboard new suppliers. This is presumably why large grocery chains have not started offering industrial toilet paper or case-packed canned goods. Some large manufacturers (e.g., Kimberly Clark) are planning, however, to switch over an industrial plant to start making a consumer product.

Yet there are successful examples of crossover from one channel to another. Many retailers have added expanded their offerings and beefed up online ordering and home delivery. Stores expanding outreach to consumers, via online ordering and home delivery, include:

- Sahadi’s, the family-owned Middle Eastern food bazaar in Brooklyn, which switched to make their in-store products available online for delivery to homes via Mercato.

- Ball Square Fine Wines, which added a produce box to their range of products for customer pickup or delivery. This essentially married a farm stand CSA concept to an upscale wine purveyor in Somerville, Mass.

- Wilson Farm, which has added toilet paper and sanitizer, sourced from the industrial supply chain, to their normal produce, bakery, meats, prepared foods and flowers.

Wholesalers serving the food service industry are now adding home customers. Baldor’s, a wholesaler traditionally serving only the food service channel in major Northeast and mid-Atlantic metro areas, now offers home delivery to households, with a $250 minimum order. Their trucks are spotted on residential streets, not just on the highways.

Small-scale producers are also opening new channels direct to consumers. In San Francisco, fishermen are now making home deliveries. Joe Conte, a fish wholesaler who normally sells fresh catch from local fishermen solely to Bay Area restaurants, told KTVU “We immediately pivoted to home deliveries” after losing all their restaurant business. This was essential, as 80% of the seafood caught in the US goes to restaurants. 11/ A large share of vegetables are also sold in restaurants. In New York City, Farm One, a hydroponic grower of specialty produce, microgreens and edible flowers for restaurants is now “pivoting from a grow-to-order model where we have hundreds of crops growing at a time to a narrower set of crops we can grow and offer to the public,” according to sales manager Marissa Siefkes. 12/

Numerous restaurant chains, in addition to Panera and California Pizza Kitchen, are offering new services to shut-in consumers: 13/

- Noodles & Co. offers Noodles Family Meals, serving four people with entrees and sides. For each family meal purchased, the restaurant donates a bowl to healthcare workers.

- Zaxby’s is offering new Zax Family Packs “specifically designed to meet the needs of families sheltering at home,” according to the restaurant.

- The Texas Roadhouse steak chain is selling ready-to-grill steaks directly to the public.

- Einstein Bros. Bagels is offering Family Meals, to feed large groups for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

- Friendly’s has launched the Family Ice Cream Sundae Kit, available through takeout and delivery.

Even national brands known for other products have ventured into the food business. Patagonia, the rugged outdoor apparel maker, has launched Patagonia Provisions to help consumers during the coronavirus time. “We’ve expanded to include products from like-minded farmers, ranchers, fishermen, artisans and companies, offering new ways to eat well while protecting the earth,” says the website, promoting the venture as “a powerful alternative to industrial agriculture.” Products range from wild salmon to organic coffee and organic ancient grain fusilli.

Food banks are another major distribution channel, that relies on the consumer and food service channels. Food banks served 40 million people in America in 2019, according to the country’s largest nationwide network, Feeding America. Now during the pandemic, food banks are helping 17 million more hungry Americans. The 200 food banks in the network are local organizations. They depend on food donations from the commercial channels, volunteers and financial donations to carry out their vital work. Inventory levels have dropped amid sharply increased demand. 14/ Television footage showing hundreds of cars lined up for food assistance in San Antonio, Texas, was something Americans never expected to see in the year 2020. This vital channel and its challenges remain one of the most poignant food stories of the coronavirus. Supplies from restaurants and other food service operators are down to a trickle; grocery stores and small-scale producers lack the staff to redirect product to a food bank.

What may change permanently

What drives our thinking about the future of food supply chains? First, we know that consumers want fast and easy access to reliable supply. Ever since Amazon raised expectations of easy online ordering and rapid delivery, starting with books, this new reality of near-instant gratification has permeated every aspect of household consumption. The pandemic is reinforcing this mindset with stay-at-home dictates that will likely continue, in some form, for a long while.

The promise of fast and agile supply chains seemed a futuristic vision twenty years ago when I co-authored the book Value Nets. 15/ Now those dreams are coming true. The online grocery service profiled in that book in the year 2000, Streamline, and its capital-intensive competitor Webvan – both of which collapsed in short order – were ahead of their time. Today, Instacart, Amazon Fresh, Mercato and other digital delivery dynamos are prospering like never before.

A quasi-permanently increased level of concern about virus transmission is also likely to remain with us for years to come. Large numbers of people who have not had the disease, possible mutations and the time required to find an effective vaccine seem to guarantee an ongoing social distancing reality.

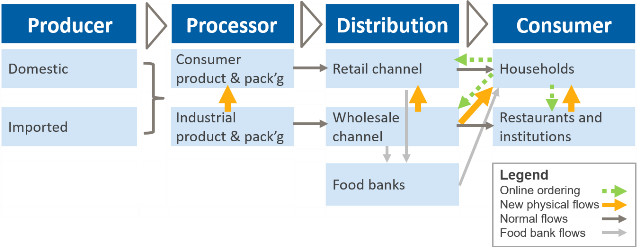

These realities suggest major changes to food supply paths (see graphic below). New online options and intensified use of existing digital flow paths for home delivery are here to stay. Crossovers from the bulk industrial channel to the retail consumer channel will also endure.

US food supply chain – as changed by the pandemic

Simplified view of food supply chain with new pandemic-related flows. Source: New Harbor Consultants.

Given this macro environment, we see five trends that will grow in prominence in the coming years:

Trend 1: More online ordering and home delivery of basic grocery items

These will include branded foods like chips, cereal and coffee; paper products; and basic health & beauty aids like shaving cream and shower gel. Consumers have established preferences for these products and know what to expect without needing to compare one offering to another. This will favor behemoths like Amazon and turbocharge a pivot to online business for grocery chains. Online grocery penetration rates will reach and sustain levels in 2020 that were formerly projected to be reached a decade from now. Of course, reasonable delivery windows must reappear to support this growth.

Jobs will be added at fulfillment centers, store order picking and home delivery. We see this already in the hiring campaigns of companies like Amazon, Domino’s Pizza and Instacart. Will order picking be moved out of stores entirely, to specialized facilities? Or will hybrid models evolve? Companies are likely to experiment with different models.

On the other hand, restaurants will face tough restrictions for months to come: Recently announced guidelines for California, once the current lockdown is relaxed, call for 50% fewer tables in each restaurant to allow for social distancing. This means restaurants will have to perfect their pickup and delivery options to remain viable.

Trend 2: Growing local food solutions

The exception will be fresh produce and higher-end products. Food purchases that depend on touch or visual inspection will continue to fuel in-store shopping. In a new collapse-of-the-middle reality, bricks-and-mortar stores that thrive must offer an experience that transcends the merely efficient procuring of supplies.

We predict that local markets offering fresh fruit, vegetables, meat and flowers will flourish. Such outlets furnish the kind of uplifting shopping experience that consumers crave. The mix will vary but the emphasis will be on providing a tantalizing display that generates sales for products beyond the basics. As people cook more at home, some will search for the freshest produce – the leeks, scallions, cilantro and striped bass – that make for delectable dinners no longer so readily accessible at restaurants. Others will patronize a local drive-in for onion rings they can’t make at home. These types of local outlets, from ice cream stands to fishermen’s co-ops, can be nimbler than chain stores in adapting to changing consumer needs.

Examples range (in the Boston area) from a modern farm stand like Wilson Farm in Lexington, to an upscale local market like Pemberton Farms in Cambridge, and an urban wine shop like Ball Square Fine Wines in Somerville. Small-scale fish suppliers in San Francisco pivoting to home delivery for consumers is indicative of the flexibility shown by resourceful local providers. Microgreen growers in Colorado, collard green producers in South Carolina and mushroom foragers in California are shifting from restaurant supply to consumer-direct models. Seasonal outdoor farmers’ markets will benefit as well. There will be new opportunities for small-scale producers to sell everything from goat cheese to grass-fed beef.

Trend 3: Automation of food processing plants and stores

Processing plants that are more automated, with less labor, will be viewed as less risky. The business case for investment in manufacturing robotics, artificial intelligence and automated warehouses will be easier to make, after the experience of plants shutting down due to illness. At King’s Hawaiian, for example, a project is addressing how to automate construction of display pallets of product, which today require a lot of labor. The pandemic will give a large boost to makers of farm, factory and warehouse robotics, such as 6 River Systems and Locus Robotics (both in the Boston suburbs).

Online order picking may be housed in specialized ecommerce fulfillment centers. Alternatively, space may be set aside within supermarkets for automated picking of the highest-moving items. Stop & Shop is preparing to open an in-store mini-fulfillment center in its recently renovated Windsor, Conn., store. The center’s 15,000 items will cover about 90% of online sales. New solutions such as Waltham, MA-based Takeoff Technologies’ eGrocery micro-fulfillment centers may increasingly be incorporated into back-of-store space at large chain stores. Such concepts can pick an average online order in less than 15 minutes. Slower-moving items can be picked manually in the store for a single combined delivery to the home. Space requirements are modest, about one-eighth of a store’s footprint. Time and cost to implement are far less than, for instance, the capital-intensive automated warehousing solution that Webvan tried (and failed) around 2000.

Trend 4: De-risking the supply chain

Companies will work to increase the resilience of their supply chains. They will shift the balance toward lower risk and away from pure low cost. The novel coronavirus is just the latest in a series of unanticipated events that have disrupted supply chains, ranging from earthquakes, strikes and floods to tariffs, 9/11 and the SARS epidemic. Steps to reduce risk will include shortening the lines of supply, adding second and third sources, addressing redundancy back up the chain to 2nd and 3rd tier suppliers, and networking plants and warehouses rather than building single or dual facilities to serve the whole US. Retailers will re-think their stocking strategies or pay a distributor to hold stock: Publix Super Markets, an upscale retailer in the Southeast, has weathered the COVID-19 storm better than other chains by virtue of using a well-stocked distributor. And companies will develop more robust contingency plans to prepare for crises requiring rapid decisions and strong communications.

Manufacturers will reduce reliance on China and other far-flung sources. After a difficult year or two of tariff battles and now the coronavirus, companies will accelerate their search for other sources of imported foodstuffs and ancillary items (containers, packaging). Replacing China with Mexico will make sense in some cases or adding a US or Mexican operation to complement a source in Asia. Within US supply chains, companies will also pull back from reliance on a single mammoth processing plant in favor of localized networks, to de-risk the food system.

Acquisitions, alliances and more flexible supply chain practices will enable easier switching between wholesale/institutional and retail/consumer channels. Simple steps, like preparing a UPC barcode that can be applied to individual items if needed or designing packaging that suit both channels, can facilitate crossover in case of demand shifts from, say, schools and restaurants to grocery chains or vice versa.

Better sensing systems, planning tools and tracking technology will be key to more resilient supply chains. 16/ Early-warning capabilities, driven by real-time monitoring of multiple indicators, will be incorporated. These can range from social media trends to virus outbreaks, daily credit card spending patterns and weekly railcar loadings. Early evidence of market trends has long been a hallmark of the fast-fashion company Zara. Companies will conduct plant and warehouse network studies with a new eye toward redundancy and recovery, adopting postponement strategies or even accepting more inventory in some cases in place of a stripped-down just-in-time model. Tracking of product flows via embedded chips and monitoring of upstream supply availability will be tightened. Information tools that support rapidly running what-if scenarios (currently offered by players like Kinaxis and Dassault Systèmes) will become much more widely used in order to assess tradeoffs and address unexpected crises.

Trend 5: New business models

New business models will arise to better manage future threats to the food supply chain. No less than seven Time Magazine covers have featured warnings about pandemics or other health crises, between 2003 and 2020. So, we are likely to face additional disruptive events in the future.

Today we see companies in the food supply chain rolling out new strategies to survive and to serve hard-hit households. These include widescale adoption of online ordering and home delivery, extensions into food from non-food offerings, cutbacks in product complexity to boost output and crossovers from the food service channel to retail.

We expect much more dramatic changes in business models in coming years. New players will emerge to marry convenience, fast delivery and efficiency. These businesses may be based on a hybrid model of smaller stores combined with automated picking of high-running food products. Delivery may utilize autonomous vehicles or drones. New packaging approaches will ensure safe food with biodegradable materials. And harvesting will be more automated while farm labor is better treated.

Wholesale food distributors will increasingly offer economic home delivery for consumers. These quantities will be larger than typical purchases at the grocery store. They will equate more to a Costco buying occasion but with the added convenience of delivery. Players such as Baldor’s, have started to tap this new consumer-direct market and others will follow.

We’d welcome such developments as a great contribution to the food security of the United States. These new business models will be supported by increasingly capable information systems and artificial intelligence to drive success. Knowing where the product is at all times, monitoring upstream supply availability and real-time sales will feed optimization tools that drive resilience as well as efficiency.

References

- How the Virus Transformed the Way Americans Spend Their Money, by Lauren Leatherby and David Gelles, The New York Times, April 11, 2020.

- Grocery delivery was supposed to be the ultimate pandemic lifeline. But it’s falling short, by Abha Bhattarai, The Washington Post, April 15, 2020.

- S. food-away-from-home spending continued to outpace food-at-home spending in 2018. USDA Economic Research Service, August 26, 2019.

- Toilet paper: The pandemic paradox, by David Bovet, New Harbor Consultants Brief dated April 13, 2020: Toilet paper: The pandemic paradox. Irrational consumers or unresponsive supply chains? .

- Share of Imports in Consumption Has Increased in Recent Years. USDA Economic Research Service, May 2, 2018.

- The Food Chain’s Weakest Link: Slaughterhouses, by Michael Corkery and David Yaffe-Bellany, The New York Times, April 18, 2020.

- An Update on How Many Days It Takes to Plant the U.S. Corn Crop, by Scott Irwin and Todd Hubbs, farmdocdaily, University of Illinois Dept. of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, April 16, 2020.

- The impact of COVID-19 on commercial transportation and trade activity, by Geotab Data & Analytics Team, Fleet Management, April 14, 2020.

- Interview with Tony Navarro, VP Supply Chain, King’s Hawaiian, by the author, April 20, 2020.

- Grocery Ecommerce 2019: Online Food and Beverage Sales Reach Inflection Point, Executive Summary, eMarketer, April 8, 2019.

- Coronavirus upends San Francisco’s fishing industry, by Amber Lee, KTVU Fox 2, April 2, 2020.

- Restaurant Suppliers Are Opening Up to the Public to Keep Their Businesses Alive, by Tove Danovich, Eater, March 24, 2020.

- Slideshow: How restaurants are reaching cooped-up consumers, by Rebekah Schouten, Food Business News, April 8, 2020.

- Feeding America Network Faces Soaring Demand, Plummeting Supply Due to COVID-19 Crisis, Press Room, Feeding America, April 8, 2020.

- Value Nets: Breaking the Supply Chain to Unlock Hidden Profits, by David Bovet and Joseph Martha, John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

- For more on building in resilience, see the ground-breaking book The Resilient Enterprise: Overcoming Vulnerability for Competitive Advantage, by Prof. Yossi Sheffi, The MIT Press, 2005.

* * * * *

Contact us to explore how we can support your strategic, operational and investment needs: info@newharborllc.com.

David Bovet is the Managing Partner at New Harbor Consultants. He focuses on helping clients translate their supply chain vision into practical results. David brings 30 years of experience across a range of industries and geographies. Projects focus on strategic direction, operational improvement and hands-on implementation. He is the co-author of Value Nets: Breaking the Supply Chain to Unlock Hidden Profits, about the power of fast and flexible logistics-intensive business models.